A visitor walking through the streets of Brownsville with no prior

knowledge of the town,would be struck by a series of feelings.

One of these feelings might be of wonder as they try to piece the

broken picture of the town together in their mind of what it might have

looked like in its heyday. Another thought would surely be of its present

day condition, ruined, empty,and quiet. How they would think, could a

town with such beautiful architecture be in such a deplorable condition?

They may in that instant, understand the immense history of this place,

a history that is hidden to most in the windowless buildings, the empty

facades, and theghost town appearance that Brownsville reflects.

As an industrial archaeologist who was born and raised in Brownsville,

the town's history is my history. I have tried to help out where ever I

could, and in my research for my dissertation, I have talked to many

folks who lived in town when it was seemingly booming. I have

encountered two types of people who live in our town, those that want

to preserve it, and those that want to tear it down. Rarely do the two

ideologies meet in the middle.

To both sides, I ask this, “what is the largest industry in the world?”

The answer is heritage tourism. By and large, throughout the world,

especially in Europe, small towns that suffered economic disasters

realized that tourists like to see old buildings especially if you could

tie an interesting history to them. Take for example in Sweden

where they reuse old dilapidated industrial buildings by turning them

into apartments. Closer to home in Michigan's Upper Peninsula,

the copper mining patch towns are realizing that there are people

from around the world interested in mining and who

travel there just to see how copper was mined.

Brownsville has three focal points to heritage tourism.

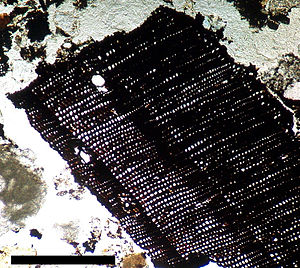

The first one is the Dunlap's Creek Bridge. As an industrial archaeologist,

I have been to conferences where the main draw is bridges and bridge

construction. Currently, most of the span is covered by previous construction.

This is not really an issue. The issue is the invasive knotweed that covers the

banks. Cooperation to have that removed during the 2009 July 4th celebration

was met with hostility from the governing body of the town. The focal point that

would generate the most tourism interest should be the bridge. People identify

easier when they are told that something is the first of its kind. The second

focal point is Bowman's Castle. It is the most easily recognized structure

on the landscape as people come across the bridge. The third resource

Brownsville has in its favor is the Monongahela River. The promotion of

the history of the river in the development of the United States cannot

be over stated, and yet in our town, few people fully understand

how Brownsville contributed to western expansion. The invention

of the western steamboat to funding the locks and dams on the

Monongahela River, Brownsville was the center of it all. Yet there is little

that a visitor new to the town would be able to discover on their own.

So what is the solution? How do we pull in visitors who may want to stay

and invest in Brownsville? First, we need local history

(with a Brownsville focus) taught in our schools with knowledgeable

people talking to the students. Second, we have to put ourselves out there.

There should be an advertisement in historical magazines touting the first

cast iron bridge in the United States. We cannot wait for development to

find us --but we have to seek it out. Third, cut the petty infighting and political

nonsense between the City of Brownsville, BARC, and the Historical Society.

This town needs collaboration not division. We can see what division has done

already and it is not an alternative. I think we need to have someone documenting

the town and coming up with a car tour or walking tour. If the building isn't there,

so what? Have a picture of it and its importance. Our town's heritage was

steamboat building, we built over 800 of the boats. We are ground zero for western

river steamboat innovation and development. Let's devise a tour based on

that, where people can see where prominent captains, workers, and boat builders

were. However, we first have to see value in what we have. If we don't feel that

Brownsville is valuable, then it has no worth. We will have a parking lot and not a

single reason to park there.

I want to invite people from all around the world to visit Brownsville,

Pennsylvania. Relish in its industrial 19th century history, and be absorbed

into its decay. Yes, that's right. I want you to come and see the decay the

20th century and its deindustrialization has done to this once thriving town.

I invite you to look at the Dunlap Creek Bridge and think about the promise

it held for the fledgling United States, and look at it now for what it is, a

forgotten artifact of the first half on the 19th century. When you come an visit,

pass judgement not on what you see today, but on what could be done in the

future to create a sustainable economy here in this town on the frontier.

Marc Henshaw (Archaeology Dude)

|

| Dunlap Creek Bridge |

|

| Nemacolin Castle |

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=57e12b5f-0658-4c61-bcba-ec5172e609c3)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=5f000ee7-0107-49fa-a69b-4699a738fa64)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=3f3f64f7-5374-4ff7-b7b4-5e93bfb92185)